How a political scandal sparked the Tour de France - and what to expect this year

With the Tour starting tomorrow, it’s time to revisit what all the fuss is about. I dive into the unlikely origins of a newspaper war amidst the Dreyfus Affair before previewing this years edition.

At the turn of the 20th century, France was gripped by two national obsessions: cycling and political polemic (something I might just share with France…). What happens when you combine those passions? You get the unlikely origin story of the Tour de France - born straight out of the country’s most poisonous political quarrel.

Bonus: you’ll also learn why the yellow jersey is yellow.

Fast forward 112 editions, and the race has become a highlight of human endurance, team strategy, and high-altitude drama. In this post, I’ll preview what makes this year’s Tour special - from its brutal mountain stages to the riders and teams most likely to shape the race - and offer my own predictions as to who’ll be standing on the podium in Paris.

But before we dive into what’s coming next week, let’s rewind to where it all began: a newspaper war, a political scandal, and a publicity stunt.

The Tour de France has its origin from an important French political event: Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer, was wrongly convicted of spying for Germany in 1894 which resulted in two camps: republicans, secularists and most of the intelligentsia (the “Dreyfusards”) demanded a retrial, while the army, Catholic hierarchy and nationalist right (“anti-Dreyfusards”) insisted the verdict protected national honour.

This fracture ran straight through the French press. One of the loudest Dreyfusard voices was Le Vélo, an influential sports daily printed on green paper and edited by the liberal journalist Pierre Giffard. But its biggest advertisers - including car magnate Jules-Albert de Dion, tyre tycoon Édouard Michelin, and bicycle manufacturer Adolphe Clément - stood firmly on the other side. When Le Vélo openly backed Dreyfus, the industrialists withdrew their funding and decided to bankroll a rival paper.

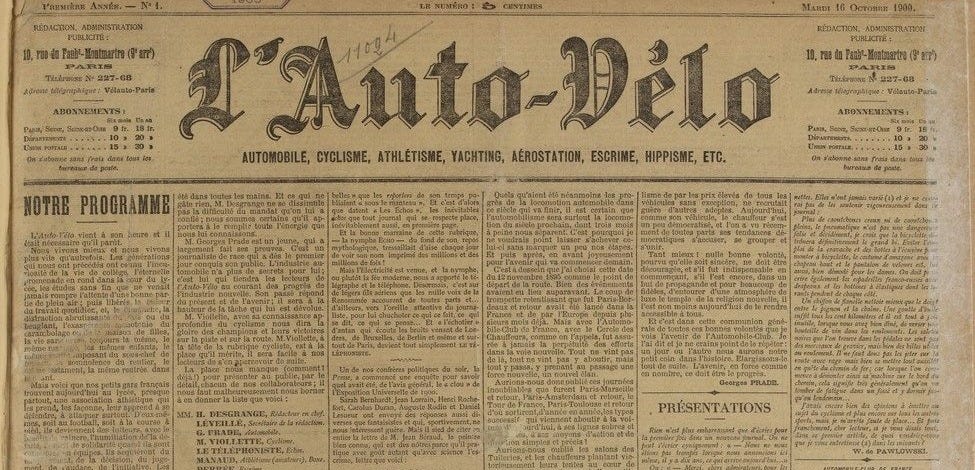

That rival, L’Auto-Vélo, launched in October 1900 under the fiery former cyclist Henri Desgrange. Its yellow newsprint was a deliberate jab at Le Vélo’s green. The paper claimed to be “above politics,” but few readers were fooled. Worse, a court ruling in 1903 forced it to drop “Vélo” from the name, leaving just L’Auto - and revealing how badly it lagged behind its competitor in circulation.

Desgrange needed a stunt - something so spectacular it would bury Le Vélo for good. His industrialist backers, thriving in the golden age of bicycles and motor cars, wanted something nationalist and modern. The idea came on 20 November 1902, over lunch in a Paris café. Desgrange’s young cycling reporter, Géo Lefèvre, proposed a crazy idea: a race around the entirety of France. The tour was born.

The first Tour de France, announced in January 1903, included six monster stages - Paris to Lyon, Lyon to Marseille and so on - totalling 2,428 kilometres. The winner was often the one who actually managed to finish - the last man standing. The entry fee was fixed at a single franc and riders were forbidden of any outside assistance so even a factory worker could participate.

Maurice Garin, the “Little Chimney-sweep”: the 32-year-old Italian-born Parisian dominated, winning three stages and leading for all 19 days to pocket 6128 francs - three years’ wages for a labourer. But the true victor was L’Auto. Its sales jumped from 25,000 to over 300,000 during the race, while Le Vélo never recovered and folded the following year. The Tour’s leader wore a yellow jersey from 1919 onward - an enduring echo of L’Auto’s yellow pages.

So, in short, the race’s DNA still holds the imprint of a divided Third Republic. The Tour de France was born not merely as a bike race but as a circulation-boosting marketing masterstroke - a risky bet that fused nationalism, new-century technology and raw human grit. The gamble paid off so spectacularly that 122 years later the whole world still tunes in each July to watch history’s longest newspaper promotion ride by.

This year - anything special?

After last year’s detour to Nice, the 2025 Tour de France starts in Lille on 5 July and, three weeks and 3,338 km later, returns to the Champs-Élysées on 27 July. It is the first edition since 2020 to stay entirely inside France’s borders, visiting 11 regions and 34 departments along the way.

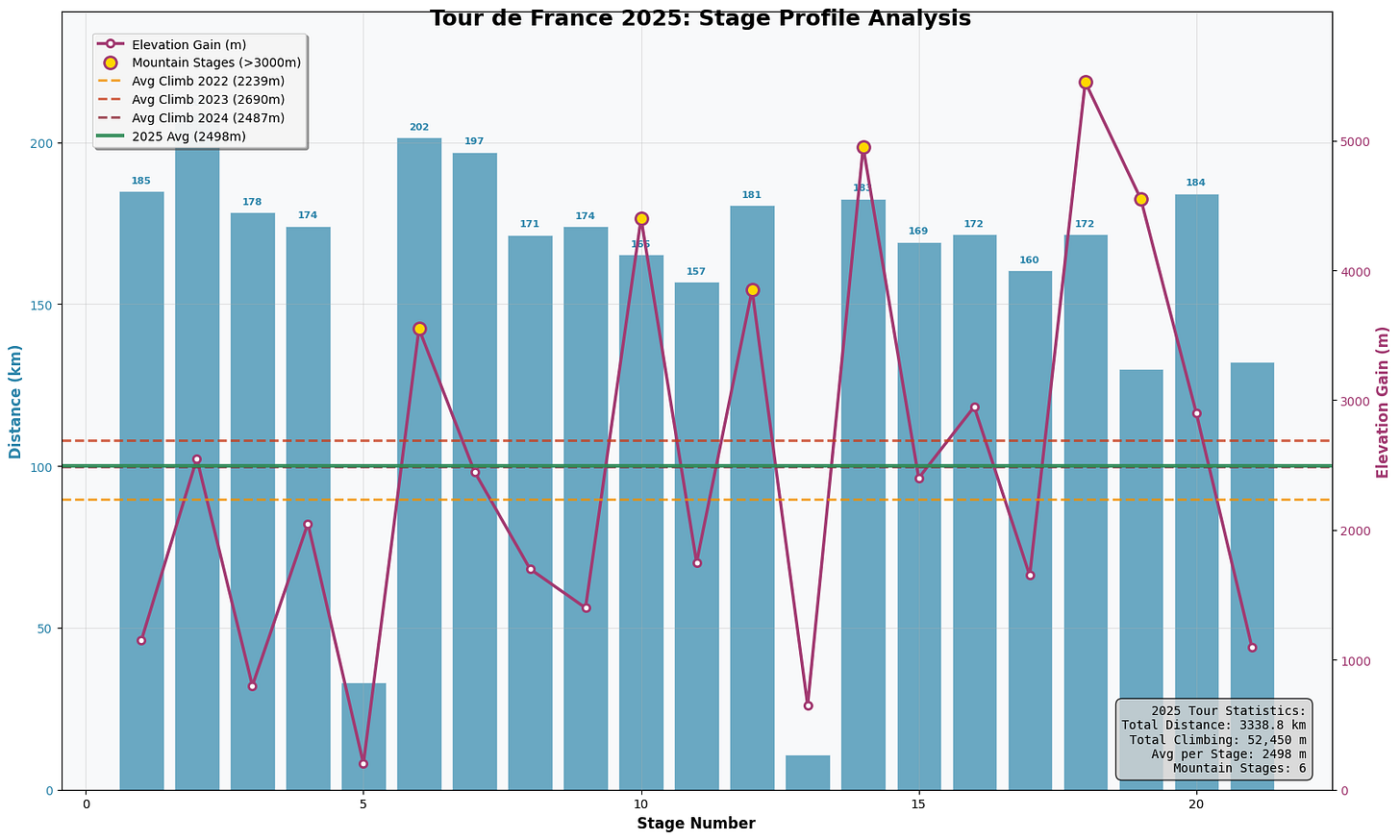

The route mixes seven flat, six hilly and six mountain stages with two time trials. Five summit finishes (Hautacam, Luchon-Superbagnères, Mont Ventoux, Col de la Loze and La Plagne) and an Everest-scale 52,500m of climbing tip the balance toward the climbers. Let me try to summarise this in a graph (excuse me for using double axis please):

The opening northern block is anything but a ceremonial parade: three circuits through the exposed plains of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, a cross-wind run down the Channel coast to Boulogne-sur-Mer and a classics-style finish in Rouen give the sprinters early targets but could also spring echelon chaos for the overall contenders.

The Tour’s first real sorting-hat arrives in the Pyrenees. Over three consecutive days the race tackles Soulor-Hautacam, Col de Portet en route to Luchon-Superbagnères and then the Peyragudes mountain time trial - just 11 km, all uphill, and likely to penalise any GC hopeful whose engine prefers long flat efforts.

Mont Ventoux headlines the third weekend: stage 16 climbs the bald, wind-scoured giant from Bédoin. The queen stage comes two days later: 171 km from Vif over Glandon and Madeleine before the brutal 26km grind to Courchevel’s Col de la Loze. With more than 5,000m of elevation and gradients hitting 20%, this day is expected to create the biggest time gaps of the race.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Champs-Élysées finish, organisers have spliced the Olympic road-race loop into Stage 21: the peloton will climb the cobbled Rue Lepic up Montmartre three times, the final ascent just six kilometres from the line. GC nerves will stay until the last lap.

Who to watch out for?

So who’s most likely to tame Ventoux and conquer the Champs-Élysées this year? Let's look at the contenders - and the teams behind them.

I expect there to be a familiar heavyweight duel between two-time champion Jonas Vingegaard and Tadej Pogačar, with Remco Evenepoel and a resurgent Primož Roglič lurking. Power-data previews still rate Pogačar as slight favourite after a dominant Dauphiné, yet Col de la Loze training sessions this month show all three primary challengers testing one another’s limits on the very climb that could decide July. The following graphic contains my bets (which I based on bookmakers and UCI points):

Then it’s time to look at support - because I cannot stress enough that cycling is a team sport. My chart below breaks down each top team’s core strengths (according to me) across three domains: climbing support, time-trial power, and sprint depth. UAE and Visma stand out for their mountain engines - crucial for shielding their GC leaders on Ventoux and the Col de la Loze - while Soudal–Quick‑Step dominates on the time trails, and Lidl–Trek leans more toward sprinting.

Another chart below shows how those same components contribute to each team's overall GC support score. With 50% of the weighting from climbing ability, it's no surprise UAE tops the chart, bolstered by its all-star climbing trio (Yates, Almeida). Visma and INEOS follow closely, thanks to their balance of climbing and TT depth. This graph summarises it:

After having watched the Tour de France from start to finish (even a couple of times at the Champs-Élysées), I can say that a lot can happen in the race which is only more reason to get hyped up for tomorrow!

A final note: while this preview focuses on the men’s race, we shouldn’t forget the Tour de France Femmes, which has rapidly become one of the sport’s premier stage races. Since its revival in 2022, it has showcased fierce competition, world-class climbs, and rising stars like Demi Vollering and Katarzyna Niewiadoma. The 2025 edition - held in August to avoid Olympic clashes - will feature expanded mountain stages and a summit finish in the Alps. As the women’s peloton gains depth and visibility, this race increasingly stands on its own merits.

![Winner of the first Tour de France 1903 [481 × 640] : r/HistoryPorn Winner of the first Tour de France 1903 [481 × 640] : r/HistoryPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!a192!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff78cc9c6-7f04-45df-9d09-17d76b3821e4_979x886.jpeg)